Just like the geographical shape of the Netherlands (allegedly) represents a lion, China represents a rooster. The head in the east touches Korea, the chest touches the East China Sea and its feathers in the south west reach up to the Himalaya. With a distance between East and West of roughly 4500km, the country is enormous and vast. With over 1.3 billion inhabitants, the highest in the world, spread over 26 provinces it is also extremely diverse.

The country counts 55 (officially recognised) ethic minorities in addition to the Han, the largest ethic group. Living in diverse natural areas ranging from deserts to jungles, much of the inhabitants are connected through a rapidly expanding high speed rail.

Upon my arrival at the Chinese embassy in the Netherlands to request my visa, I thought I had come prepared sufficiently with my general vague itinerary of how I’d spend my days. However, it turned out that this was not quite sufficient. To request the visa, I had to book all accommodations and transport for the entire 45 days and with only 30 min left on the clock.

There was one tiny computer for emergency use, which no doubt had ever been operated this franticly. After a ferocious protest by my niece, it was time to go. I would stop by in London (5 euro bus ride Eindhoven-London!) before I’d fly out from Heathrow.

I also know now, that flying just after being struck with an English flu (they called it an Australian flu) is not a great idea. Getting weaker and weaker during the flight, I had turned into a lifeless dishcloth upon arrival in Shanghai, my first city in China.

Shanghai

Thankfully, fate decided that the parents of a girl who I had met in Vietnam a few months earlier, Delinda, were willing to take me into their home in Shanghai. They couldn’t speak much English, or any really, but they did made sure that my bedridden body was being fed with delicious home-cooked meals until I recovered.

About a week later, I joined millions of Shanghainese on their daily commutes and I was able to catch a tiny glimpse of what commuting in Shanghai can be like. Apparently the train doors don’t politely wait until the passengers have gallantly entered or exited. Their imminent closure decelerates for no one, and as it turns out, including me. I’m glad my worried I’m-going-to be-squashed-to-death-face was able to amuse some of those inside who tirelessly deal with this every day.

-

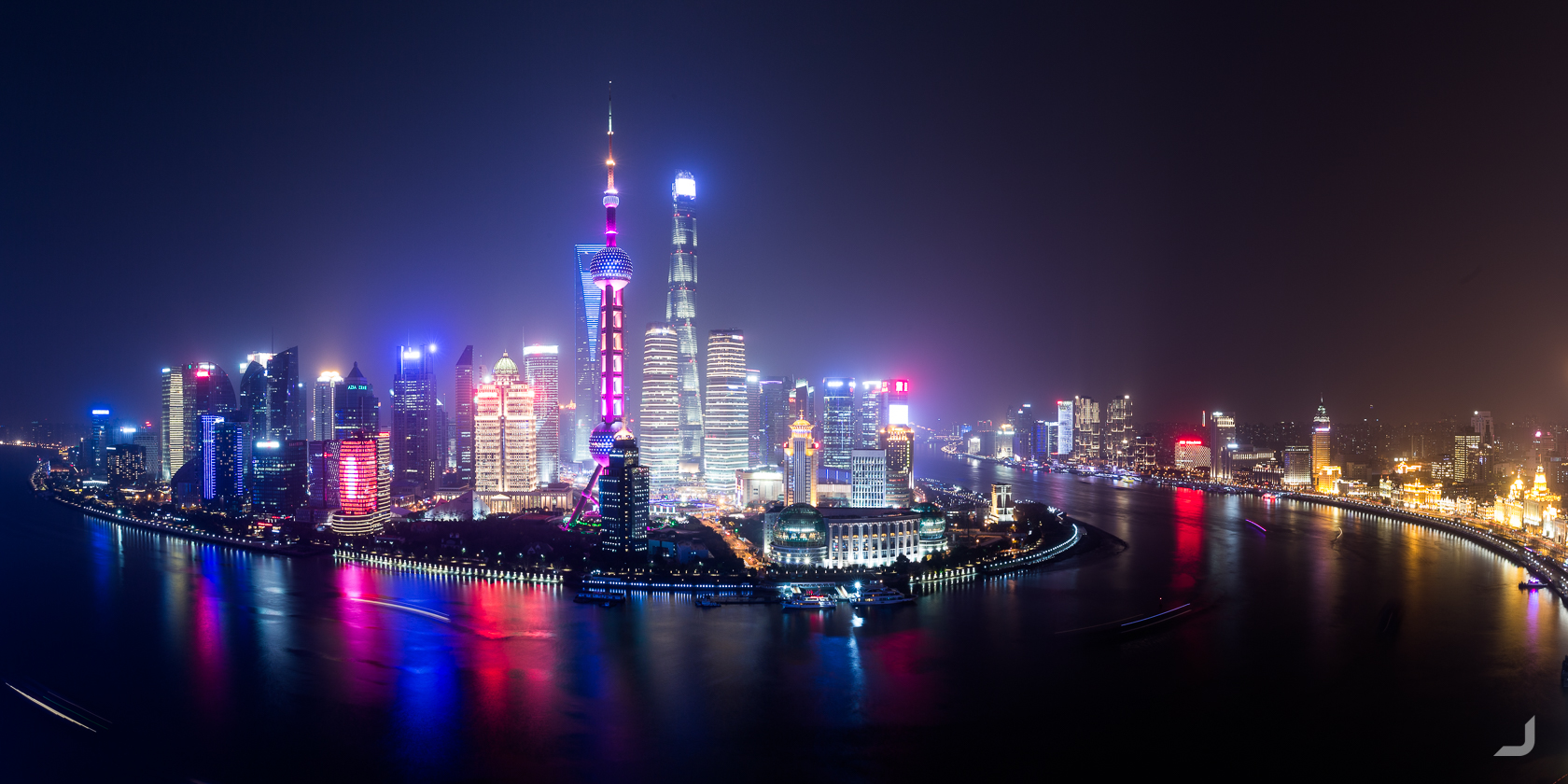

Shanghai Huangpu River

China

A long exposure of a boat passing by in front of the Shanghai skyline.

Shanghai skyline view taken from the rooftop of a hotel on the Bund, a scenic waterfront area along the Huangpu river.

Regardless of my lack of knowledge of the local customs, in some places I didn’t really need to do anything awkward to gain attention. My tall and lanky appearance already did that for me. One lady jumped on a busy street just to take a picture of me from the front. I feared for her life and I’m sure this would’ve become evident in her picture.

Technology had creeped into the Chinese way of life as if it had never been any different. Nearly all payments were made using the mobile phone and some restaurants would go as far as to only allow orders and payments made using this device. Perhaps the Chinese had strived consistently to get the latest of available technologies but then cheaper, on their own terms and for a strict purpose only. Cameras were on every corner tracking every movement, electric cars and scooters zoomed the streets and neon lights and tv screens coloured most of the taller concrete buildings. Yet every now and then an elderly farmer on a cargo bicycle would slowly cycle through the midst of the busy traffic, reminding us that this digital transformation couldn’t have happened too long ago.

Déqīn

The Chinese government allow foreigners to visit Tibet for a limited period a year (which wasn’t at the time I was there) so the plan became for Delinda and me to travel to the Tibetan border as close as possible, approaching from the south through the Yúnnán province. Passing by the Tiger Leaping Gorge, according to the Lonely Planet a top hike in China (and also a place where the Chinese had their own interpretation of how English should be translated and where neighbours don’t like dirty cars spoiling their streets), we continued further north along the G214 highway until we reached Déqīn. Déqīn is the last Yúnnán county before Tibet. From there, we found a van that would take us to Xīdāng, the start of the path to Yǔbēng. Yǔbēng is a small and little known village inaccessible to cars and an excellent starting point for hiking the snowy mountains of the Meli Snow National Park. We arranged for the same van to pick us up 3 days later and were able to leave our bigger bags under their care.

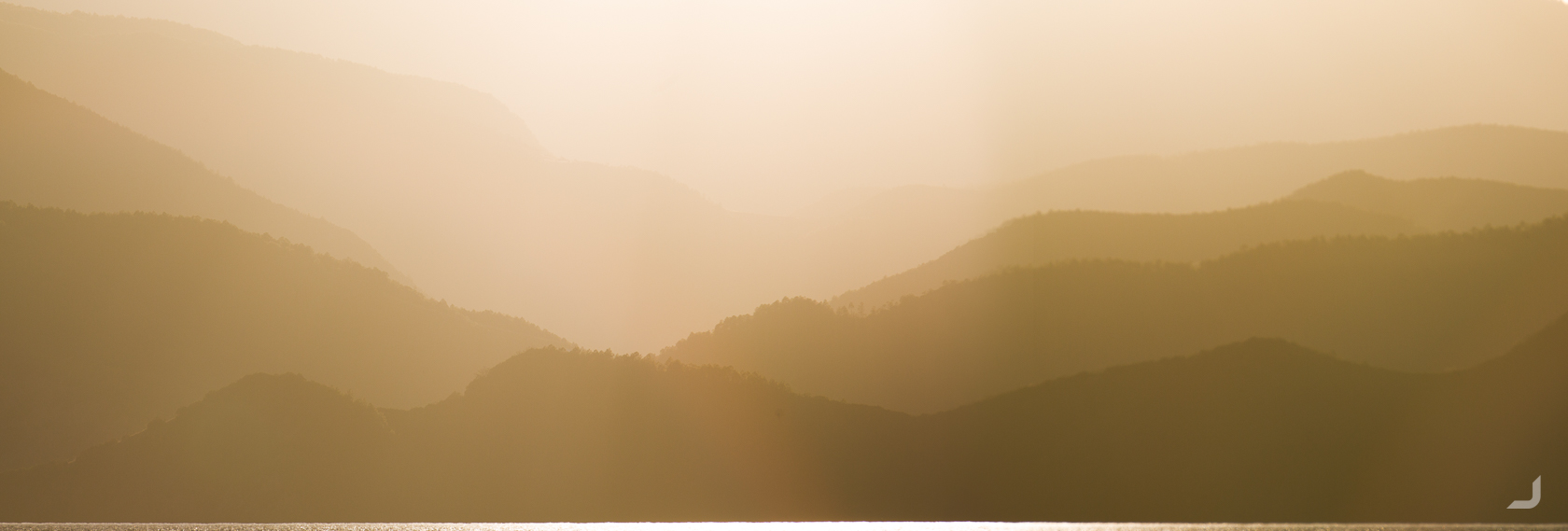

The mountains in Yǔbēng, a small secluded town inaccessible to cars.

Yǔbēng

There were 3 recommended hikes starting from the (upper) Yǔbēng village; the path to the Glacial Lake, the Waterfall and the Lake of God, all between the three and four thousand meters. The “Miancimu” peak is the most imposing peak of them all. The views along the walks were breathtaking and were usually accompanied by colourful Buddhist flags with in-scripted prayers in Sanskrit, aimed at keeping travellers safe. They also frequently marked the end of a long steep climb and together with the often ensuing views made every sight of them an absolute joy. Some higher peaks featured rock walls covered with money for good luck.

After 3 days of hiking through the snowy mountains surrounding Yǔbēng, we descendent back to civilisation via a different path. The snow had slowly made room for sand and the narrow path along the steep sandy ridges lead along a deep river cut valley. The occasional monk passed by, followed by a donkey transporting goods, against a rather surreal and contrasting industrial mining backdrop.

As we reached the rendezvous point, it quickly became clear that something was wrong. The driver who was there to pick us up, having our bigger bags in his car, told us that we wouldn’t see our bags again unless we paid a lot more money. It reminded me of a small town in the north of Vietnam, where I was looking for a place to eat and handed someone a business card with the name of a restaurant to ask if he knew where this was. “Money!” was his reply. I would only get this business card back if I paid him some money. Before I could realise that he was serious his friend took the card from him and gave it back to me. However, in this case there was no sensible friend present. Luckily, Delinda knew how to get so angry that he promptly opened the trunk to our bags.

Shangri-La

Leaving the Déqīn area by bus (where seemingly some passengers have no trouble wearing balaclavas), we traveled further down stopping in Shangri-La. In Shangri-La, hotel room doors don’t quite close the same way as I was used to. It is also home to many monasteries, surrounded by mystical mountains and was originally named Zhōngdiàn. It was later re-named after the fictional land of Shangri-La in the popular novel Lost Horizon to promote tourism.

Bǎijī Sì monastery, known as Hundred Chicken Temple, surrounded by mystical mountainous in Shangri-La.

Old Town of Liǔjiāng

Further down south lays the “Old Town of Liǔjiāng” or “Daya”, a small historical city centre known for its ancient houses surrounded by waterways and tiny bridges. Although it is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site, it sometimes hard to look beyond its “modernisation” with lights and reconstructions and to discover its authentic soul.

Daya, or “Old Town of Liǔjiāng”, has a history of more than a 1000 years and its houses are surrounded by swirling waterways.

Lúgū Lake

Taking a quick detour to Lúgū lake, the highest lake of Yúnnán and marked by many islands and peninsula’s.

Looking out over the Lúgū lake from Gesa, north east of Shangri-La.

Travelling further south along the G214 highway towards Dàlǐ, not too far from the Burmese border, every now and then a fake police officer would keep an eye on the traffic or cellular towers can be spotted hidden in trees.

The mountains slowly turned into a pale sandy brown with a blueish horizon, reminding of a similar hue covering the Blue Mountains in Australia.

Dàlǐ

Dàlǐ is the ancient capital of several kingdoms before it was conquered by the Ming Dynasty in the 14th century. One of the main sights in the old centre are the Three Pagodas of the Chóngshèng Temple, dating from the time of the Kingdom of Nanzhao and Kingdom of Dàlǐ in the 9th and 10th centuries.

The main pagoda, Qiānxún pagoda, was constructed in the Quanfengyou period (825-859 A.D.) of the Nanzhao Kingdom and is one of the tallest pagoda’s in Chinese history.

The three pagoda’s have remained relatively unscathed throughout history. During the most recent earthquake in 1925, only 1% of the buildings survived but the pagoda’s managed to remain completely undamaged.

The houses in the Old Town of Dàlǐ must conform to the traditional Chinese style, covered with tiled roofs, built using bricks and plastered or white-washed walls.

The Chóngshèng Temple is located right behind the three pagodas, which previously functioned as the royal temple of the Dàlǐ kingdom. The temple itself didn’t lend for a nice photo, however a couple of pure white doves were up for the challenge.

-

Dali Dove

China

Dozens of white doves take shelter underneath the distinctive Chinese roof tiles of the Chongsheng temple.

Dàlǐ has been predominantly Buddhist throughout history; 10 out of its 22 kings retired to become monks. Though other minority cultures and religions managed to establish here too, including Christianity.

The Trinity Catholic Church was built between 1927 and 1932, combines Bai and Han culture and was listed as a cultural preservation site in 1985.

After Dàlǐ, Delinda returned to Shanghai and from then on I’d be on my own. It quickly became evident that it was going to be harder than I thought.

Kūnmíng

When I tried to check into my hotel in Kūnmíng, the receptionist yelled something in Chinese and he had absolutely no patience to type it into on my translate app. I had no choice but to call Delinda and hand over the phone to the receptionist. It turned out that my room was no longer available and I had to walk down to another hotel a couple of blocks away. As I walked down, the streets became darker and the neon lights became more colourful and brighter. I eventually found the new hotel, in which each room started with the number 8 for good luck. My room was completely lit by a giant red neon 大 that was hanging outside the window. It was so bright that the curtains didn’t make a difference. I was also kindly suggested to contribute to the local economy with a couple of business cards with pictures of ladies laying on the table.

I hadn’t eaten yet and I found a small restaurant across the street. The family running the restaurant looked at me like they had only seen Westerners on tv. There was no menu and even if there was, it probably wouldn’t have mattered. Again I had to resort to a call with Delinda who could suggest the owner what to prepare. This wasn’t setting a great precedent.. what if I wasn’t able to lean on her in the future? I would find out, plenty of times.

Pǔgāo Lǎozhai

The Yuányáng Rice Terraces had been on my list ever since I had met a traveler in the Philippines who spoke highly of these wonders of human engineering. The area is close to the north of Vietnam and features similar distinct mountains which are often covered with layer upon layer of rice terraces.

Xīnjiē was the first stop I had to get to before I could continue to the smaller villages. I aimed to stay at the same village as the traveler had suggested: Pǔgāo Lǎozhai. A town where women don’t shy away from carrying heavy things, men enjoy the waterpipe and children’s haircuts are precise.

At dawn I was able to receive my first glimpses of the rice terraces around Pǔgāo Lǎozhai that would reach as far as the eye can see.

Pǔgāo Lǎozhai is a small town surrounded by rice terraces that have been cultivated by its habitants, the Hani people, for at least the past 1300 years. According to locals, when clouds develop it looks like “a stage for the ladder leading to the heaven”.

The rice paddies are perfectly levelled before it can be flooded with water. Otherwise some rice seedlings could be too high or too low.

The bottom of the rice paddy consists out of hard clay that will prevent the water from seeping through. On top of this clay, a softer layer of mud is placed in which the rice seedlings will eventually be planted exactly 6 inches apart. Before the paddy can be flooded though, the field requires to be perfectly levelled.

A local Hani in front of her house.

There is not much time to rest in Pǔgāo. Even when not attending the fields, fertiliser needs to be created, seedlings need to be nurtured, the irrigation systems needs to be repaired and after one harvest, the next requires to be prepared.

A Hani lady repairing clothes.

This Hani lady spotted me from afar and was very keen to be photographed providing she would be reimbursed. I paid her the amount she agreed to but the light reflection from the floor was too strong and I had to adjust the camera after a few failed attempts. To her it didn’t matter and I had to pay more if I wanted to take more pictures. I was not very good at arguing in Chinese so I did.

Sporadic ducks are collected and transported over the terraces by a Hani farmer.

There are several stages to rice terrace farming. Firstly, seeds are planted (or transplanted, planted somewhere else and then moved over) in a perfectly levelled terrace where water is kept at exactly the right height. The terraces will look like tiny pools which could result in photogenic reflections. Then when the rice grows taller the fields will slowly turn green and then yellow when the rice is ready to be harvested.

A Hani farmer smokes a waterpipe.

-

Pugao Rice Terraces

China

A farmer is levelling the field (bottom right) at one of the many rice terraces in Pugao.

-

Pugao Sunrise

China

When there is little wind the terraces turn into immaculate mirrors.

-

Pugao Farmer

China

A Hani farmer walks over the land when clouds are approaching fast in the background.

According to a local sign post, there are a 156 houses and 770 villagers in Pǔgāo Lǎozhai, of which I wonder how up to date this information is. It also mentioned that the ancestors of Pu’s Clan moved here and gave it its current name Pǔgāo Lǎozhai.

A Hani farmer walks along one of the many narrow paths along the ridges of the terraces, that could sometimes be a real challenge to find for non-locals like me. The ridges themselves can be unstable and slippery, as I found out first hand when I slipped and dipped my camera in the muddy water. I pulled it out as fast as I could and at first it looked like the landing force displaced the water enough to have survived the worst; only leaving a camouflaging layer of mud. However, the manual focus wheel now required the Hulk to be operated.

Around the more touristy locations, it was always a challenge to find a good vantage point to take pictures from. There are a few dedicated spots where, naturally by now, one can enjoy the view for a fee. Then it is survival of the tallest, though a tripod can greatly spoil this advantage in a blink. Outside of these paid views, entire stretches are either blocked by enormous view-blocking boards or by policemen directing rebel photographers to the paid locations.

Once the sun has set, the busses that brought the mostly domestic tourists in are just as quickly gone, frequently catching me by surprise how quickly it can go from extremely crowded to no people at all.

At Bada, one of the more popular locations looking out over the fields it was no different. As soon as the sun had set, the place was deserted in no time. Reality hit when I realised getting a ride back to Pǔgāo was rather unrealistic and I saw no other option than to start walking the 10km back, along the dark and windy road. I tried my luck by sticking out my thumb and a couple of girls stopped to let me in. They drove me back to my hostel while singing along to a Chinese tune on the radio.

As much as I would’ve liked to, I couldn’t stay too long amongst these villages as my 45 day visa was nearing its end. An option was to try to extend the visa but for that I had to visit the embassy back in Shanghai. So I booked my flight from Kūnmíng and I had to make my way back up, via Mile and Luoping.

Mile

Mile is a small city with lots of little alleyways hidden amongst the busy streets. Some stores compete with each other to see who can play music louder to “attract” customers. It has also the worst name to find any extra information about it.

An accidental heart shape emerges on the wall of one of the alleys in Mile, Yúnnán, China.

Luoping

Luoping is famous for the cone like hills that are scattered amongst rapeseed flower fields. I didn’t quite yet know where to stay and ended up walking into a random boutique hotel run by an elderly couple. The rooms looked like they were built in the 50s and hadn’t changed a bit since.

Cone like hills are surrounded by rapeseed flower fields in Luoping, Yúnnán, China.

In fact, I was so impressed with the frozen-in-time art deco interior of the hotel that I tried to take a photo. However, to counter the bright light from the windows I had to adjust the exposure a few stops down. Unfortunately, I forgot to turn it a few stops back to 0, rendering all my following photos of the hills and the fields a few stops too dark.

-

Laoping Hills

China

An 8 second exposure of the rapeseed fields in Luoping, Yúnnán, China.

It is always easy to get somewhere when leaving from the city. Taxi’s are easy to find or the hotel can help with ordering one. Also Didi, the Chinese ride sharing app, has no trouble finding a ride in crowded places. Returning to town on the other hand can be a little trickier. This time I was instructed that I could take a specific van back to the city from a very unspecific location somewhere alongside the road, that didn’t feature any sign posts.

In good faith, I waited close to an hour before a man dressed in black noticed me and started lurking around and staring at me from a distance. At one point he asked me something in Chinese, I replied “Luoping”, the name of the city I had to return to. He came closer and ended up waited with me, in silence and for about another 30 minutes, until he flagged the right van down for me.

Nearby Luoping, the Jiulong Waterfalls are located which features some impressive layers of falling water.

One of the taller layers at Jiulong Waterfalls nearby Luoping, Yúnnán, China.

After Luoping I returned to Kūnmíng to catch the flight back to Shanghai, to extend my visa. At the embassy, the lady behind the counter asked me whether I was aware of the fact that tourist visas cannot be extended. “No” I answered. “Why do you want to stay longer?”. I had to think for a moment. “Because China is too big” I answered. While rolling her eyes she reluctantly approved the extra 30 days that I requested.

Huángshān

It meant I could visit Huángshān or “Yellow Mountan” near Shanghai next. That day it was extremely foggy and I wasn’t able to see any of these (yellow) mountains. It turned out that the fog clouds the mountains about 360 days of the year.

-

Huangshan Pine

China

Huángshān pines, unique to this area, commonly grow on alpine peaks which are from 800 to 1,800 meters above sea level.

Wūzhèn

Visiting Wūzhèn, another historic town slightly south west of Shanghai and supposedly over six thousands years old.

The houses in Wūzhèn are surrounded by waterways. Looking relatively serene here, long exposures can be deceiving.

Waterfront in Wūzhèn.

A bridge covering one of the many waterways in Wūzhèn.

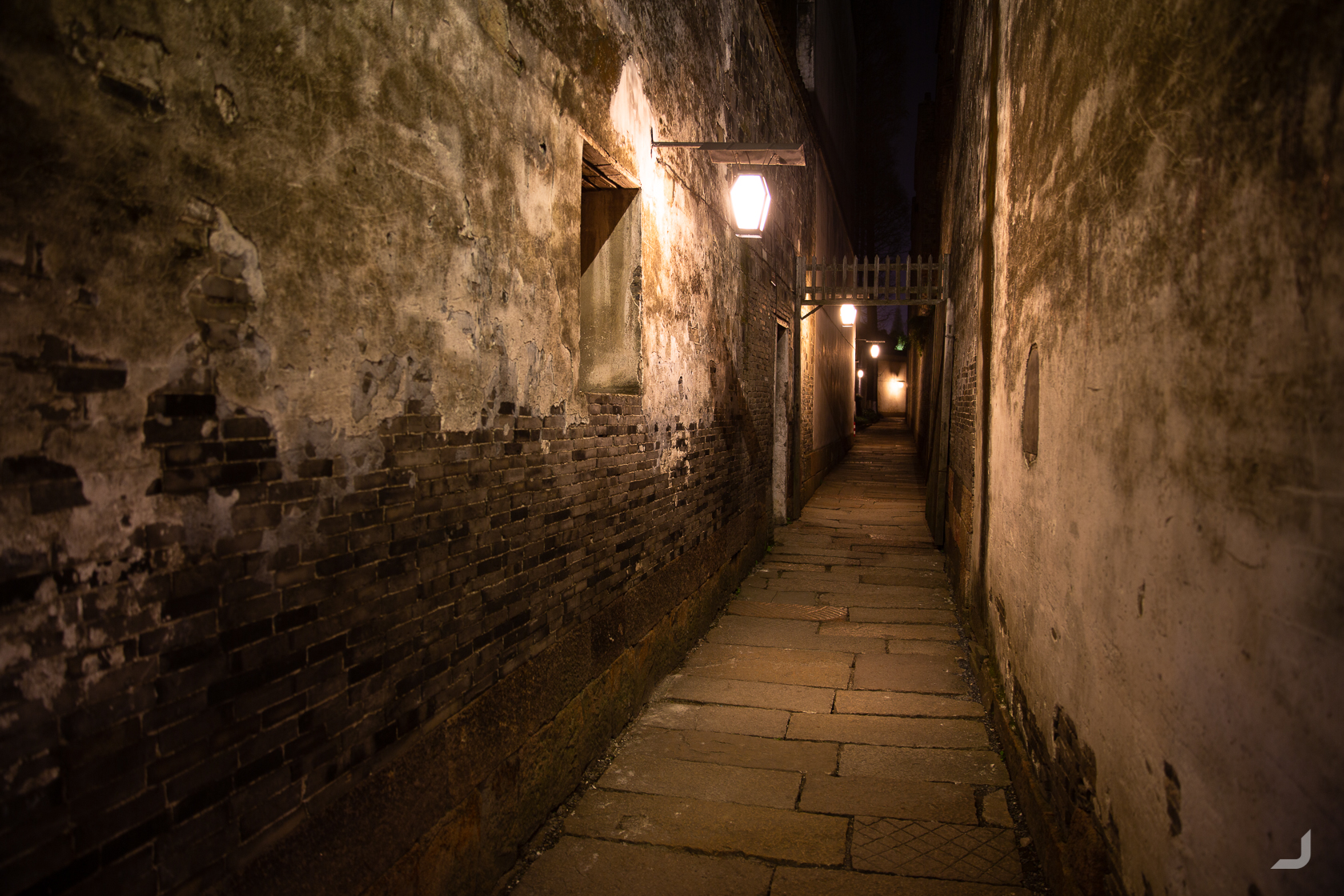

A dimly lit alley within the maze of Wūzhèn.

One of the walls inside Wūzhèn.

A long exposure of one of the bridges in Wūzhèn.

Wūzhèn waterfront.

New buildings are still built in the old historic style, though not quite using the old techniques. They are built almost entirely out of concrete (which also became quite evident in Emeishan).

A brand new temple and pagoda in Wūzhèn.

One of the older houses along the waterfront in Wūzhèn.

Another long exposure of one of the alleys hidden in Wūzhèn.

Shanghai

From Wūzhèn, I returned to Shanghai before I continued to Zhāngjiājiè, Guìlín, Yángshuò, Chéngdū, Xī’ān and Běijīng.

3 of Shanghai’s most famous skyscrapers: Shanghai Tower (bottom right), Jin Mao Tower (top right) and Shanghai World Financial Center (bottom left).

Zhāngjiājiè

Zhāngjiājiè is home to thousands of jagged quartzite sandstone columns, which very much look like the fictitious environment in the movie Avatar by James Cameron.

The world’s longest outdoor elevator, called Bailong, leads to the upper path. The lift was filled to the brim with domestic tourists and at the moment the view cleared after the lift had departed there was as communal “ahh” that could’ve made the average person hearing impaired.

Zhāngjiājiè is home to thousands of jagged quartzite sandstone columns, many of which rise over 200m.

It took me a while to find the hostel that was mentioned in the Lonely Planet. The sun was about to set and all busses had stopped operating long ago. When I finally found the place, along the corner of small road, it was completely abandoned and the windows were barricaded. For a moment I didn’t know what I should do next, returning to the city was not an option. There might be accommodation just outside of the park, but even walking there might take the whole night. Even if I would arrive on a fairly decent time, there was no guarantee that they would have a room available. Maybe I should just try to find a space in the forest?

Along the same road, just before the corner, I passed a home that had a smaller house next to it looking a bit like a mini-motel featuring several doors in a row though no signage to be seen. I walked up to the main home and knocked on the door. A elderly lady opened and said something in Chinese I couldn’t understand. I mimed the universal sleeping gesture, hoping she would understand that I was looking for a bed. She walked me to the smaller house and opened the first door. There it was: a double bed, a bathroom and even a TV.

I gestured whether she had any food, upon which she asked me to follow her and she led me to a small wooden shed where she gestured me to sit down. After a while, her husband came in with one after the other dish with rice, vegetables and soup. I was saved.

Zhāngjiājiè contains thousands of sandstone columns.

Fènghuáng

After Zhāngjiājiè I took the bus to Fènghuáng, a tiny scenic town on the way to Guilin where I was unexpectedly greeted by a colourful romantic hotel room.

Waterfront in the Fènghuáng Ancient Town.

Houses along the Tuojiang river in Fènghuáng.

Yángshuò

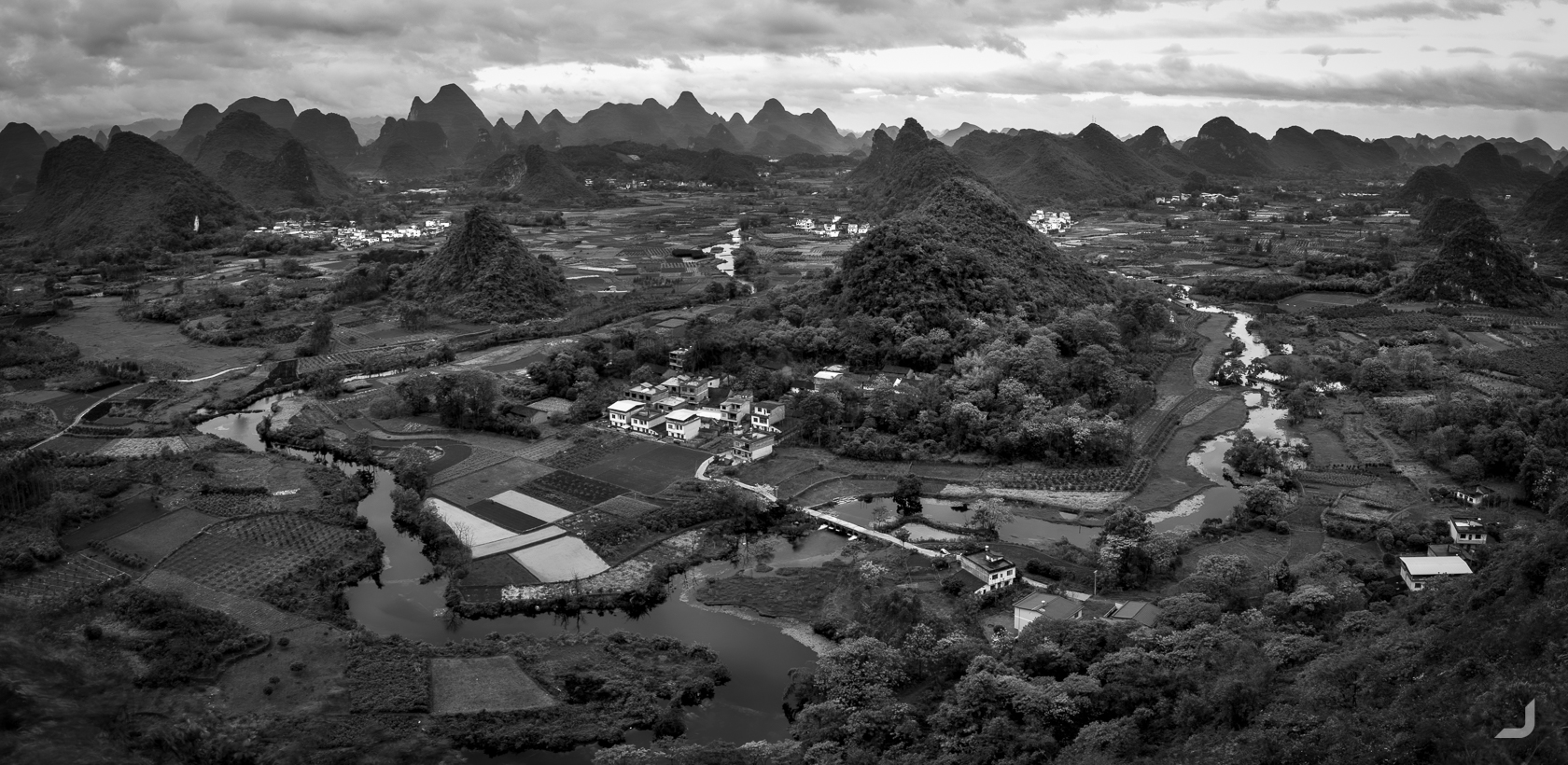

Moving further down to Guìlín and Yángshuò, home to many dramatic karst mountains.

I went twice to this location at the Cuiping village, as under the right conditions this view has the potential to lead to a fantastic image. But both times I was greeted by thick clouds and rain. A gloomy black and white photo is the result.

When hiking up a mountain in Xìngpíngzhen, it was getting a bit hot and I tried to pull off my scarf. It didn’t quite want to go off and when I finally succeeded I understood why it was so difficult. I had inadvertently pulled off my camera along with the scarf and now I had to watch my little baby tumble down the stairs in slow motion. When I picked it up the body still seems to work but the lens seemed wrecked. Now I only had a zoom lens left, and I was about to see a panoramic view.

Luckily, there was a camera store in Guìlín that was able to fix the lens for a lot lower price than I had feared.

Lóngjǐ

Visiting the Lóngjǐ Rice Terraces north of Guilin. The rice terraces of Lóngjǐ were largely unknown to the world until in the ’90s a photographer documented the area with stunning images.

-

Lóngjǐ Farmer

Australia

A rice farmer tends his rice terraces in Lóngjǐ.

Panoramic from the Nine Dragons and Five Tigers viewing point in Lóngjǐ.

Yángshuò

I wasn’t yet finished with Yángshuò and returned in the hope to take better photos under hopefully better weather.

The view of the west side of Yángshuò city at night.

I had heard of the cormorant fishermen at Xìngpíng who were eager to pose for photos as they were no longer able to make a living from fishing the way that they used to. In Guìlín city, nowadays local actors had resorted to act as cormorant fishermen by standing up with a cormorant, a large type of bird, when a tourist boat floats by.

I asked a hostel how I could get in touch with one of the original fishermen and they were able to connect me to 白胡子, or “white beard”.

黄全德, or nicknamed 白胡子 “white beard”, demonstrates how he used to catch his fish with a net.

Cormorant fishermen use the cormorant to catch the fish for them. When the bird returns to the boat the fisherman can stroke the neck causing the bird to regurgitate the fish, hence catching the fish.

-

White beard

China

黄全德, or “White Beard”, is a cormorant fisherman just like his dad. He is one of the last fishermen alive who has actually practiced this craft in the past to make a living.

Chéngdū

I continued north to Chéngdū, where pandas in the research and breeding centre make you think that your camera is broken.

A panda rests inside the panda research and breeding centre.

The narrow shopping streets of Chéngdū are alive and thriving, featuring pig’s noses, offering services like getting your ears cleaned and of course every corner has a plush panda for sale. At some stores visitors can hire traditional costumes of which a professional photographer will then take photographs. As I walked by, I was able to hitchhike along with one of these photographers.

A lady in traditional Chinese clothing in Chengdu.

Éméi Shān

About 200km south of Chengdu lays Éméi Shān, or Mount Emei (Shān means mountain), one of China’s four sacred Buddhist mountains. About half way up, I bumped into a German couple and we continued our walk together. As we made our way deeper into the forests and higher up the mountain more and more monkeys expressed their interest in us humans.

As the night fell we found a place to sleep at one of the monasteries alongside the mountains. In the morning, I was woken by the smell of incense and the sound of chanting monks. At our departure, a monk advised us to find and carry sticks to help us defend against the cheeky culprits. I could not have underestimated the need for these sticks more. At one stage a group of monkeys ganged up behind us and one of them reached out to grab the German guy by the leg. He just managed to turn around and use his stick to fend them off. I frantically tried to use my stick to help him out while grabbing my phone to film the ordeal. This was another level.

A pagoda looks out over the clouds at the top of Éméi Shān, or Mount Emei.

Xī’ān

Xī’ān is one of the oldest cities in China and is home to the famous Terracotta Army.

The detail of the Terracotta Ary is incredible. Some 8000 soldiers were buried, along with 130 chariots with 520 horses, and 150 cavalry horses around 210-209 BCE with the purpose of protecting the emperor in his afterlife. Each of these soldiers features a unique face.

The Xī’ān City Wall is one of the oldest, largest and best preserved city walls in China. It was built in the 14th century under the rule of the Hongwu Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang.

Běijīng

From Xī’ān, I took the high speed train to Běijīng, literally “Capital of the North”, which would be my final destination. I ventured out to Mùtiányù, one of the best preserved sections where the Great Wall of China can be accessed. It was a cold and rainy day and not many tourists could be found.

-

The Great Wall of China

China

The Great Wall of China at Mùtiányù.

The Great Wall of China measures a total of 6,259 km of wall and is recognised as one of the greatest architectural feats in history.

When I arrived at the wall, I had the option to turn either left or right. I first turned left and I ran into a small group who had just finished an 8 hour walk, indicating that the walk could continue on for a while. When I turned to the right, the wall appeared to end after a short walk already. Then I noticed that a small window in the last tower (which can be also interesting on the inside) had a make-shit set of stairs leading down. It lead to a path that continued on a branched, totally unrestored section of the wall.

The earliest stretches of the Wall were being built from as early as the 7th century BC by ancient Chinese states. This section at Mùtiányù was first built in the mid-6th century during the Northern Qi and was rebuilt in 1569. Most of this still stands today and this section is considered as one of the most preserved sections of the Wall.

As I returned to explore more of the left side, it slowly started to get dark and the amount of people around me went from only a couple to absolute zero. I texted Delinda to ask if she knew what time the last bus would depart. She replied “4pm”. It was already passed 6pm by then. Thinking it wouldn’t make a difference anymore I continued my walk for another hour. For a split second I thought I’d have to stay the night in one of the towers, which would have been quite a story to tell, but I was less than unprepared for a cold and rainy night on a stony surface.

I made my way back down to the now deserted entrance, that was the scene of bustling activity only a couple of hours ago, and checked my Didi app for rides. None came up. I had no other option than to start walking towards the highway and hope that someone would pick me up. As I came nearer to the main road I spotted a fairly dodgy looking man standing next to his car who had noticed me too, visibly questioning my presence.

I walked up and asked if there was a chance if he could take me back to the city. He said he could take me to the closest train station for 300 yuan. Didi had advised just a bit earlier that it would cost around 300 all the way to my hostel, so it seemed a little expensive. For a minute I tried to bargain, but I quickly realised there was no point and I agreed.

I sat next to his daughter in the back, which strangely helped in hoping that he actually would take me to a station. It was a near 2 hour drive and I just made it in time for the last train, which was another hour and a half. It was quite the final adventure of the total adventure that had been China.

No other country had been as much as a challenge to visit, but also no other country had been as rewarding. I had come a little closer to the ultimate goal of being able to be dropped anywhere in the world, and still know how to get around, still know how to be alright.

This post was my third and final instalment of my year of travels, to discover local projects and NGO’s for Fair Photo and to take nice photographs. Unfortunately, I couldn’t focus as much on local projects in China as I could in other countries. Partly because China doesn’t like allowing such projects as it would expose weakness in their own government and partly because focussing on photos and getting around (without speaking the language) was hard enough already as it was.

On my previous journey that lasted 6 months, I got tired of wearing the same 5 t-shirts over and over, not being able to sustain close relationships, not having a home, not having savings and not having a future career. This time, however, was the first time in my life that I had come to accept my life on the road as it was, and I could have kept going. But the time had come to return to Sydney to repair the financial damage, progress my career in design, work on the Fair Photo website and of course, save up for my next journey, where ever it may lead.